How To Write About Family

If you read all my published work in lit mags, you'll notice I did not write about family incredibly often, at least not directly. But they always sneak in. They flaunt their dark humor in my metaphors, they sigh in the negative space between lines, they wear the titles like a sundress—laughing—feet in the grass and light in their mouths.

First, some context.

I have 2 brothers and 10 sisters.

My parents are very religious (washing of feet and speaking in tongues before going to the buffet across from Walmart type of religious), which was one of their main motivations for adopting 7 kids after having 6 of their own.

This…experience…first led me to nonfiction. In college, I'd write lyrical essays about a small army of girls pruning the thorny invasive Russian Olive trees that grew wild all over our property. I wrote about my mom losing her mind, not suddenly like they do in the movies, but back and forth—lost and found and lost and found and lost and—

Then when I began publishing my fiction and poetry, I started using my pen name, Isabelle, in part because I'm a teacher and I don't need a 16-year-old student to find a poem I wrote about "slick little death after death," but mainly because I wanted to hide my family and hide from them.

So how did I overcome this particular obstacle to the point of being audacious enough to write a newsletter titled, How To Write About Family? How do you write about family?

Be bold. Own the story. It happened. Don't let anyone tell you it didn't happen. Be honest. And go back. Go back to the past and unearth the tangled roots of your family.

It's painful. Writing about family feels like holding the wrong end of a knife. You want to let go, but you can't stop clutching.

But if a topic or a theme keeps resurfacing, it's because it needs to. You need to let it out and write it down.

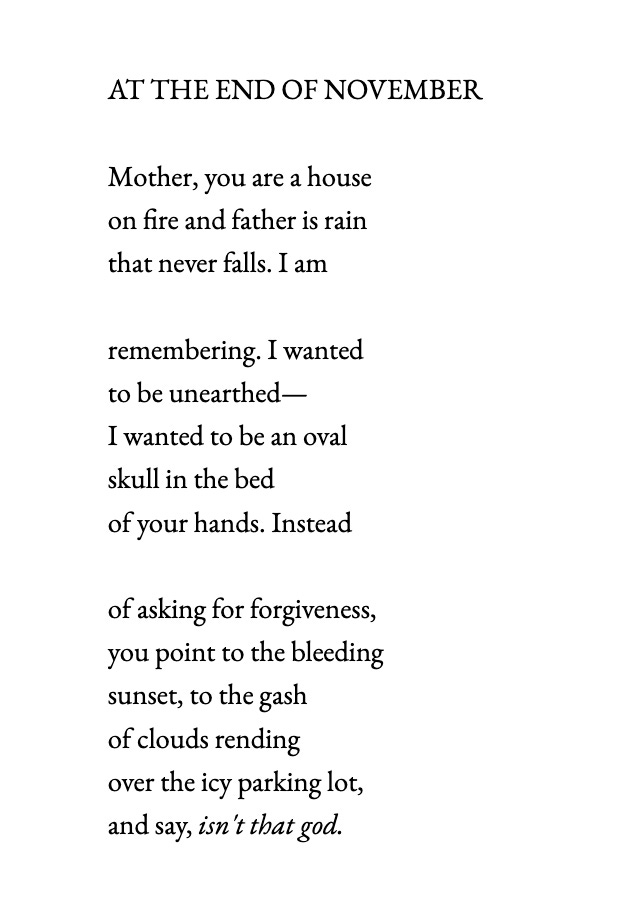

For me, this is done in two ways: listening to my dreams and never throwing away any lines. In the poem I'm sharing below, I heard the first three lines clearly and several times in a dream in November of last year when I was home visiting for Thanksgiving. And the final stanza where my mother points to the sunset and says, "isn't that god" was a real-life moment from 12 or 13 years ago. I'd written that moment down 12 or 13 years ago in my journal and in prose poems, and the imagery even made its way into some fiction I wrote for school. I didn't know what it meant exactly—my mom giving credit to god so casually yet firmly, saying the question like a statement—but then I was 32 in my niece's bed at 3 am the day after a heart-wrenching argument with my mother, the kind you should only have once or twice in your whole life, the kind where you point to your wounds and beg for understanding, and then there was the moment of the sunset like one piece of the puzzle and the words from the dream like another.

That sunset (which truly was incredible, sprawling, and ridiculously pink like a raw open wound) became a way of understanding the cognitive dissonance my mother used to survive. In her mind, she didn't hurt anyone; god did. And in her mind, that would always be so.